by Laurel | February 20th, 2013

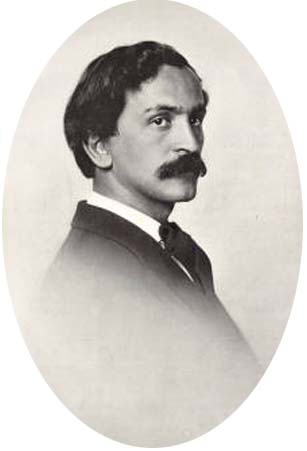

The Liberal Layman’s Club of the Connecticut Valley was organized in Northampton, Massachusetts on November 15, 1898. The objectives of the club were to encourage friendly relations among the liberal churches in the Connecticut Valley and to promote the interests of the liberal faith. The membership consists of gentlemen of Unitarian and other Liberal churches in the Valley. Rabbi Charles Fleischer was b. Breslau, Germany, 23 Dec. 1871. Coming to America in 1880 he was graduated at the College of the City of New York in 1888 and from the University of Cincinnati in 1893, and rabbi from the Helven Union College of Cincinnati in the same year. In 1894 he succeeded Rabbi Solomon Shindler at Temple Israel, Boston, where he remained until 1911, founding in the latter year an independent religious institution, known as the “Sunday Commons” of Boston, of which he has since been leader. He is also known as a lecturer and contributor to magazines and newspapers. He wrote “American Aspirations” (1914). Interesting to note the sizable crowd who attended this lecture and some of the recognizable Holyoke names.

05 December 1901

Address to Liberal Laymen

Interesting Discussion of “Mass Ethics” by Well-Known Boston Preacher.

The quarterly meeting of the Connecticut Valley Liberal Laymen’s Club was held at the Franklin at Holyoke last evening. A company of about 75 men sat down to dinner, and following the repast an address was given by Rabbi Charles Fleischer of Boston on “mass ethics.” T. M. Shepherd of Northampton presided, and a committee was appointed to bring in a list of officers to be voted on at the next meeting of the club. This and the election of secretary to fill the place of W. W. Peck of Chicopee, who was obliged to leave early in the evening, constituted the business of the evening, and the time was almost wholly taken up by Rabbi Fleischer’s address. Among those present were V. E. Cleveland, C. C. Tracey, J. H. Clagg, George S. Graves, E. B. Brewster and Messrs. Brewer, Ware and Graves of Northampton; Rev. Alfred Free of Florence, Rev. J. D. Read, Capt. Davis. F. E. Wells, J. W. Stevens, and A. L. Wing of Greenfield; Rev. Bradley Galman, George M. Demson, D. E. Webster, F. W. Dickinson, H. R. Johnson of Springfield; Rev. A. Singsen, L. P. Nash, James Ramage, T. S. Childs, Mr. Summer of Holyoke; F. E. Bigelow, C. Schadee and G. M. Blaisdell of Chicopee.

Rabbi Fleischer’s address was heard with much interest. Ethics, he said, may be deemed as the science and art that is the theory and practice of right human relationship. Mass ethics, then, would be the theory and practice of correct conduct on the part of masses of men, that is, of men acting corporately, whether as societies, communities, sects, or nations. Individual ethics has to do with relations of a single individual to the rest of mankind, whether one or many. Mass ethics has to do with the relations of bodies of men with one another, or with single individuals. As an illustration of the present disparity between individual and mass ethics, we may quote the matter of capital punishment “Thou shalt not commit murder,” is the injunction obeyed by the individual; but as a mass, a commonwealth, we do commit murder. We do in a body without a twinge of conscience, what as individuals we would not be permitted to do. “Thou shalt not steal” is obeyed by the individual but as a corporation we lose our souls and enter into enormous schemes to rob our fellow man.

Individual ethics such as we now hold represent ages of social evolution. They are nott a “revelation” which burst out upon a peculiar people, having in a some now insignificant part of this earth’s surface. Rather they are a gradual, a very slow development, representing ages upon ages of adjustments of human individuals to one another. The organization of men into masses, whether in races, nations, tribes, clans or families, is a very recent event in the history of man. “A thousand years are in they sight as yesterday when it is past,” the psalmist says, and certainly the same holds true in the story of the progress of man.

As each new mass unit comes to be a part which is taken for granted and of which we are no longer constantly conscious, the ethics, the moral ideals, also come to be fixed, and standards of right relationship among the various groups are established. A new complexity enters into the combination when not only individuals but masses enter into relationship.

It is very evident that we are in the very throes of a mutual adjustment of individual and mass ethics. that many still say, “My country right or wrong,” that a member of a nation will all himself the indulgence in sentiments and practices as an individual he would not allow himself is simple and patent enough proof of the fact that we have not yet adjusted individual and mass ethics. We shall no longer dare to say, “My country right or wrong,” but we shall say “My country must be right as God gives us to see the right and my country dares not be wrong whilst we, the people, the individuals who make up the nation, can see the right.”

We have not yet reached that plane of human development. Rampant nationalism is now a fact. I believe it to be only a transient phase of social evolution Nationalism is practically a new sense, almost a product of the 19th century. Here in America, nationalism, this new sense comes now to the mass of all these different elements that have gathered from the ends of the earth to made America, and is not yet a completed sense. The last three years, with all that the contain for many of us, of events and incidents which we deeply deplore, have yet been worthwhile when viewed from the higher standpoint as contributing toward this sense of nationalism. We ought to regard nationalism particularly as it concerns us here in America, as an onward step, the next larger combination.

Let us remember all the history that has gone to make up the possibility of the present moment, in which we of differing sentiments, different races, different religions, different nationalities, different births, are here assembled in one place, patiently, even sympathetically, to hear each what the other has to say, and listening reverently, almost prayerfully, if perhaps out of this combination of all these varied elements there may come to us a perception, keener and more comprehensive, of the all embracing truth. Let us consider all the history that has gone to make up this moment. Let us know all that has gone into American nationalism, this welding of varied elements into one nation, and who will say nationalism is not an onward step? In this way we may see the possibility of combining men into larger and larger units making gradually for the progressive realization of all the social possibilities of the human race. America, thus viewed, is a striking, hope-breeding example of the possibility of subordinating even mass differences and mass peculiarities to the national idea, and in turn to a higher and more progressive, more inclusive ideal.

Browning says, “A people is but the attempt of many to rise to the completer life of one.” If we are disappointed, as many of us are, in what has transpired in the United States during the last three years, it is because we have not remembered the fact that America is not peculiar in needing to be born, to be sent to the political kindergarten, the primary school, the grammar school and the university, before being graduated into the real life and business of a nation.

We should not forget that we, too, must have our mass experiences, that America, too needs time in order to rise to the greater life embodied in the ideal teaching of Washington, of Jefferson, of Lincoln, of all the great moral heroes of our American nation. Let us understand that humanity, too, as a mass, must pass through the same progressive unfoldings, facing and conquering obstacles and rising finally to such heights that from them the individual differences shall become small and subordinate, because of the human unity which, at that height, we perceive to be the most real human fact.

And yet I would not be too hopeful even of nationalism if I feared, as, however, I do not, that human development and mass ethics will stop at this national organization and national sense.

No one of the progressive mass units is an end in itself. Let us examine them. — family, tribe, sect, nation, race. The differences and complexities are not to be solved or resolved by amalgamation or extermination. It is not necessary to the development of the next progressive unfoldment to sacrifice the sacrifice the previous phase, but merely to subordinate it. Americanism is not consistent with the strong sense of a high unit, one of which many are already conscious, and to build which already the human coral insect of highest type is very eagerly busy. That unity is total humanity.

This phrase, “the human coral insect,” is in a way unfortunate, but serves to correct a common misconception. It has been said: “Brotherhood is a fact not indeed to be built up but simply to be recognized.” Beautifully true, figuratively, but not practically true. In reality, brotherhood remains to be built up, to become a fact in every individual soul, before it can be a fact outside thereof.

It is said that there is no individualism except Robinson Crusoeism. I would say that there is individualism. My individuality and yours is the dearest, the most cherished fact in our human self-consciousness. Self-preservation is the first law of physical nature, and that law is not abrogated as the human being develops, unfolds mentally, morally, spiritually. We are not to become a conglomerate jellyfish mass of human beings, but we are to remain distinct individualities. Emerson says regarding friendship: “We are to be very two before we can be very one.” So I would say concerning marriage, that not only is the woman not to “obey” the husband, but she is to become in that new relation a distinct entity, contributing through her peculiar nature, through the expression of all that which is hers in contradistinction to that which is man’s, she is to become an individual of part of this beautiful relationship — not any more the clinging vine, the parasite fastening itself upon the manly oak.

In all our progressive human relationships, individuality is not to be lost, but to be continued, only constantly expanded. One, of course, is a man. the Jewish teacher Hillel has said “If I am not for myself, who will be? But if I am only for myself, what am I?” So always comes the sense of a larger social unit, but always without the sacrifice of the individual or even the smaller mass unit.

The mass sense grows — family, class, clan, tribe, nation, race, religion — these are only so many words symbolizing the progressive growth of human relationship. The ethics of each of these phases of social development is first felt, then it is slowly progressively thought out, uttered, and finally accepted in theory and increasingly lived.

Let us be patient. Let us reckon with the time element in moral growth. Let us not, however be patient with purposed and willful expression of might in the face of a knowledge of what is right. Let is not be patient with an insensitiveness in the mass which we would not countenance in the individual. Let us never permit society do that which you and I will not do. Let us, for example, never supinely allow the human race to murder, whether by capital punishment of in war, when we individuals have outgrown the habit of mutual murder and slaughter. Let us never be patient with an injury that the mass of men allow themselves to do to a moral law, which we as individuals already reverently recognize. But still let us be patient, seeing that, with each unfolding of the social spiral, as the social relations grow more and more complex, there comes a new element into our social intercourse. In each instance the ethics stating the right social relationship will need to be perceived by the seers and uttered by the sayers before it can be done by the mass of doers. thus we may be broadly optimistic, facing present and future.

While it is true that mass ethics are simply the extension and application of individual ethics, yet it takes time for the mass to realize this very patent truth and for the unit, the smaller unit, to subordinate itself in each case to the larger unit without self-effacement, to yield gladly to the claims of the universal ideals f truth, justice and love, and to acknowledge their inevitable application under all conditions and circumstances.

In a word, the development of mass ethic should mean not a lessening but an increasing sense of individual moral responsibility, through the culture of the ethical intuitions and the study and practice of right human relationship in all one’s intercourse with his fellows in all the complex interests of life.

Adapted from The Springfield Republican.