by Laurel | November 3rd, 2014

03 June 1945

By Professor Marian Hayes

(Miss Marian Hayes, assistant professor in the department of art and archaeology at Mount Holyoke College, has made an intensive study of industrial architecture in the Connecticut Valley. In the following article she discusses the development of and changes in mill house in this area.)

A little over a century ago the industrial revolution began to change the face of the Massachusetts reaches of the Connecticut valley. In England industry had been attracting workers for several decades to the great industrial centers like Manchester and Birmingham. In 1780 Samuel Slater began work in Pawtucket, R. I. on what was to be the first successful water mill for cotton in the United States. Rhode Island was soon dotted with textile factories. Working with Slater for a while was Peter Dobson, who had been smuggled out of England in a hogshead to escape the stringent laws intended to prevent the skilled mechanics from leaving the realm. Dobson move inland to Vernon, CT., and helped give impetus to the development of the mills in Rockville.

Others carried English methods to various parts of Massachusetts and New Hampshire. New England at the turn of the century was still essentially agricultural. Even in Boston the portrait painter Copley maintained a farm of several acres on Beacon hill until his departure for England at the outbreak of the Revolution. Travelers to the Connecticut valley after the revolution and on into the 19th century describe the quiet charm of the towns and their pleasant rural surroundings with scattered farms lining the roads. This situation created an initial difficulty for industrial developments. The determining factor in the choice of sites was water power to run the machinery. Often the desired water power was found in regions practically uninhabited or at best thinly settled. Machines with the held of water power could perform wonders, but not without workers to man them. Manpower and woman-power (as it frequently turned out to be in the textile industry) must be attracted in large numbers and quickly to an entirely new way of life. Shelter must be provided for hundreds of workers close to the mills in localities where only a few houses existed. This necessitated the building not only of mills, but of whole towns with homes for married workers, boarding houses for single men and women, stores, assembly halls and even churches.

Waltham, first of the new textile towns to be financed from Boston, was such a success that the Boston capitalists, encouraged by their profits began prospecting for new sites. Lowell on the Merrimack was the next important venture, but almost at the same time Edmund Dwight succeeded in interesting the Boston men in the power to be obtained from the upper falls of the Chicopee river then included in the boundaries of Springfield.

Typical Layout of 1825

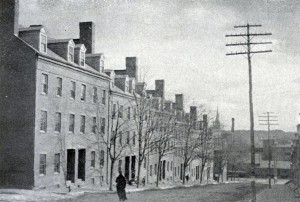

Work began in 1825 on this project which later came to be known as the Chicopee Manufacturing company (now Johnson & Johnson). The layout is typical of mill sites of the period with the mills and their adjuncts — bleachery, storehouses, repair shops and such — arranged along the river and canals and he tenement blocks occupying the adjacent land. Here at the Falls the Chicopee River makes practically a right angle turn and all the buildings are set on the flat land bounded on two sides by the bend of the river and on a third by the higher ground which rises steeply from the valley.

Most of the tenement blocks are still intact but some of the earliest mill buildings ave given way to ore modern structures. Mills and tenements alike are simply but strongly built. The tenements are only 2½ stories high as in the early ones in Lowell. Also like Lowell is the use of double houses on West Main Street instead of the continuous rows adopted in the later developments partly for reasons of economy and used here in the houses lining Middle Street. Except for an elaborate decorative pattern of bricks along the cornice line these houses are utterly devoid of decoration. The long rows mush have been more effective without the meager porches added to their front doors. Ser close to the street line as in city schemes, these tenements have spacious yards to the rear.

All these houses and the early mills of the Chicopee Manufacturing Company were built by Capt. Charles McClallan. When the Boston capitalists were looking over the ground in Chicopee Falls, they had the good fortune to come upon McClallan, then a young man in charge of a mill that was building. So struck were they with the “originality and force of his ideas and the readiness of his computations” that they employed him to build mills, dams and tenements in Chicopee Falls.

Builders for Future

Charles McClallan was born in Lancaster, in 1803 and at 18 came to Springfield to start in life for himself “with no other capital,” as The Springfield Daily Republican put it at his death in 1879, “than his own ingenious brain and vigorous spirit.” Charles Stearns of Springfield, builder and bricklayer to whom McClallan was apprenticed, made him a foreman after only two years and entrusted him with several important jobs. McClallan moved to Chicopee, went into business for himself and in 1886 formed a partnership with his son.

Charles McClallan and Son continued building brick factories and tenements. In 1872 they built the granite facades of the Hoosac Tunnel. In 1879 they had the reputation of having built more stone dams than any firm in the state, and not oe of their dams had been destroyed. Capt. McClallan built the first water works in Chicopee, the New Haven Water Works and the “Siphon” section of the Boston Water Works. His form had construction as far afield as Augusta, Georgia.

A brief notice in the Chicopee news in The Springfield Daily Republican during Capt. Mac’s last illness in June, 1879, reads: “There is no man in town who would be missed more than Capt. McClallan, for he has been identified with all the town’s interests for man years … He has not accumulated a large fortune, but he will leave behind him what is worth more than that, an unsullied reputation and the name of having won the esteem of every man that ever worked for him.”

The task undertaken by McClallan for the Boston capitalists was a Herculean one. Suddenly and quickly there must e constructed dams to provide power, factories to house the new machinery, and tenements and boarding houses to shelter the men and women gathered from hither and yon to operate the machines. The scheme in many ways is si similar to that followed in Lowell that mills and tenement blcks in the two towns seem to come from the same blueprints.

Many Contracts

So well satisfied were the owners with McClallan’s work in Chicopee Falls that they gave him contracts also for all the work in Chicopee for the Dwight Manufacturing company (now Industrial Buildings Corporation), for the Lyman and Hampden Mills and tenements in Holyoke and the Glasgow Mill and tenements in South Hadley Falls. (Although each of these projects was controlled by a separate company, the stockholders in each were approximately the same group — Cabot, Dwight, Appleton, Lyman, Perkins and others whose names still designate streets in Holyoke and Chicopee.)

A surprising number of these houses and mills are still standing and are an impressive monument to Capt. McClellan. According to the writer of his obituary notice the man and his work can be described with the same adjectives — “unpretentious, genuine, honest and strong.” Time has borne out the writer’s opinion of the buildings, for after a century most of them are still in use. The walls and foundations are strong and in excellent condition. Only the rapid technical advances of the past century and the consequent changes in our manner of living have made the interiors of the tenements seem outmoded. Many have been modernized with the addition of plumbing, electricity and other improvements which were not considered requisite for living quarters in he mid 19th century.

For their times these lodgings were adequate and comfortable. the rooms were large and light, the ceilings high. Probably they were pleasanter than the homes from which many of the girls had come. They represent a remarkably enlightened and benevolent paternalism on the part of the first leaders of industry, which characterized the early phases of industrial development all over New England. To be sure, the mill owners had to provide some sort of houses, but they might have been satisfied with less substantial buildings.

However standards of buildings were generally high at the time and so the quality of the construction many have been dictated partly by the necessity of offering attractive quarters to the young daughters of farmers and the Yankee artisans who were the first to work in the mills. Every inducement was made to lure workers to this new kind of life and the attractiveness of the rooms must have contributed. The crying need for labor did not mean, however, that the company was prepared to hire all comers. A printed notice signed by Agent Cumnock of the Dwight Manufacturing Company in Chicopee states, “The company do not design to employ and who are intemperate or immoral in their habits, or who are habitually absent from public worship on the Sabbath.”

Regulations were strict for all residents in the company buildings. The following rules from a list issued by Agent Lovering of the Lyman Mills in Holyoke toward the end of the 19th century are typical. “The hall doors must be closed at 10:00 o’clock p.m., and no persons admitted after that time without some reasonable excuse.” Tenants shall not allow the defacement of rooms by pasting hand bills or pictures of any sort on the walls, nor shall they allow the driving of nails into the plaster or woodwork./” “Tenants must be prepared for the inspection of their houses at any time.”

Supervised Employees

The concern of the companies was by no means confined to the physical preservation of their property. Every protection was given the young women in the boarding house where all from out of town were obliged to live. These houses were owned by the companies and under their constant surveillance. They were presided over by carefully chosen and eminently respectable women whose responsibility for the physical and moral welfare of their charges was out of all proportion the the meager pittance they were able to wrest from the slight margin between income and expenses. Young women were expected to be decorous in their behavior and to attend worship on the Sabbath, as they would doubtless have done at home. Their wages would incredible to the modern ear — $1.75 a week — but in addition there were opportunities to improve the mind by reading and lectures sponsored by the company.

In Cabotville (Chicopee) the Olive Leaf and Factory Girls’ Repository was a semi-monthly publication. The Cabot guest might be had for one dollar a year in advance. Both carried articles of unquestioned respectability but of perhaps doubtful literary value. Whatever may have inspired the solicitude of the company for its employees, there is bo doubt that it was very real. Brick sidewalks, for instance, were built so that the operatives might avoid getting their feet wet and in many other ways the companies constantly showed their concern for the workers.

Since most of the stockholders in the local textile mills lived in Boston their affairs had to be managed by a representative called the agent. The agent was responsible for the operation of the mill and its adjuncts including the residences for the workers. He lived in a mansion convenient to the mills but slightly removed from the tenements and more elaborate in detail. The agent’s house in Chicopee (now occupied by the Polish-American Veterans club) is typical. Surrounded by spacious grounds the house stands at the end of Perkins Street. The agent could look from his front windows down the street between the lodging to the main entrance of the mill. His house symbolized in its position an architecture the authority of the agent over the mill property. The house is of brick and essentially simple but the low broadly projecting hipped roof is supported by twin white wooden brackets of a type used in some Lowell houses. A cupola surmounts the roof in the center.

Simple Tenements

The tenements downstreet are much simpler with only the white muntined windows and a pattern of brick work on the gable end to break the austerity of their plain brick walls. Even the porches which add so much to the charm of the Chicopee houses are recent additions. But there is a justness about the proportions and a soundness in their craftsmanship which related these houses to a deep-rooted American tradition of sound building. The unity of the layout of mills and tenements stems from 18th century town plans like Williamsburg and a host of European predecessors. The buildings represent the end of the Georgian style which had dominated American architecture for more than a century and which now was adapted for a brief period to new and strange purposes. They mark the close of an era, but already the seeds of the new technical age have been sown in them.

About the middle of the 19th century profound changes began to affect American life and that of the whole western world. In the textile industry native sources of labor were inadequate to supply demands. In the Connecticut Valley as elsewhere the demand for more hands was met by the importation of foreign labor — Irish, Canadian French and Polish — beginning in the late 1840’s/ The tremendous implications of this and many other changes are reflected in the architecture of the later 19th center. No longer is there the unity of a homogeneous Anglo-Saxon tradition. No longer is there the certainty about style or standards of craftsmanship so obvious in the earlier houses — this, of course, was a situation prevalent all over the western world to some extent.

Mills in the last quarter of the century mad advances in technical matters such as lighting and ventilation, but fell prey to the same disintegrating forces as other buildings, Ornamental towers with Romanesque details or French mansard roofs punctuated their otherwise simple silhouettes replacing the simple early cupolas which helf the bells to call the operatives to work. The mansions of the mill-owners announced their enormous profits with galaxies of towers and tons of gingerbread.

More and more the mill workers were left to shift for themselves and were often forced to live in miserable jerry-built slums. Such tenements as were built by the companies show a distinct falling-off in quality. In Chicopee rows of houses were inserted between the original ones crowding the yards more than they were intended to be. These houses are of brick to the top of the first story, clapboarded above. They have more ornament applied to their walls and gables than the earlier ones, but the typical 19th century quest for style and picturesqueness has robbed them of the serenity of their earlier brick neighbors.

Early in the 20th century the Dwight manufacturing company, in need of further housing facilities, erected wooden rown houses and tenement blocks on Dwight terrace or Sand Hill in Chicopee. The houses have a fine view and modern conveniences (as of 1915), but they are bleak and uninteresting by comparison with the structure in the town below.

Recently in 1940 when it was proposed to improve housing conditions in Holyoke, it was decided to tear down the old tenements between Lyman and John Streets and use the bricks for the building of Lyman Terrace. The walls and foundations f the old structures were in good condition, but the internal arrangements of the houses were peculiar and, for modern purpose, inconvenient. As in the case of some of the Chicopee blocks a single apartment might consist of two rooms on each of four floors, and arrangement not unsuitable it the upper rooms were to be occupied by boarders, but not so handy for occupancy by a single family unit, no matter how large. This and other groupings of rooms may be responsible for the destruction of many of the houses after they war since they make renovation difficult.

As we approach a period of great building activity at the close of the war, our ideas of architecture as of other matters are still in a state of flux. There is much to be learned from the old mill buildings in our midst about integrity of craftsmanship, unity of planning and dignity of line. These principles, lost sight of in the scramble for style in recent decades, are coming to the fore again. The new buildings will be different in detail and in general appearance — more sophisticated, perhaps. But if any percentage of them achieve the standards met by McClallan’s work, we can well be proud of our efforts.

Adapted from The Springfield Sunday Republican.